Rise of passive investments creates pitfalls

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The march of passive investing has been one of the defining themes of asset management over the past decade. But advisers warn that certain rich and risk-averse investors could run into trouble by relying too heavily on these products.

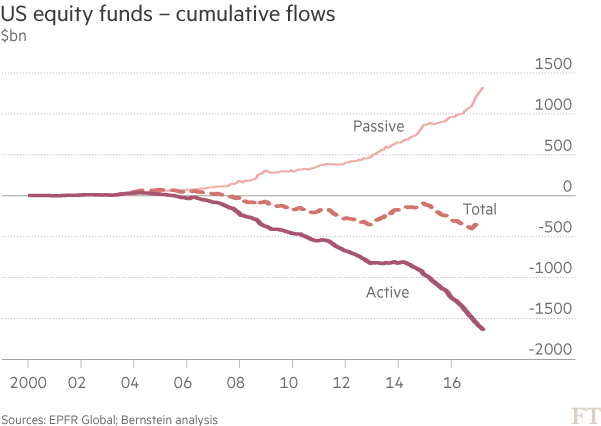

Passive investments, such as index and exchange traded funds, are expected to make up more than half of equity assets managed in the US by January, according to a recent report by Bernstein, a research company. US actively managed funds experienced net outflows of $340bn last year, while $505bn flowed into passive vehicles, says research provider Morningstar.

The change is being driven in part by years of underperformance by active managers. In the 15 years to 2016, almost all US large-cap, mid-cap and small-cap fund managers underperformed their respective benchmarks, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices, after their fees were taken into account.

For most investors, the focus on passive vehicles makes sense, experts say. “You can’t control the ups and downs of the market. So it’s generally better to go with the market and capture those returns than to try to bet against it,” says Max Holvik, investment research manager at Private Ocean, a California-based registered investment adviser.

However, other advisers argue that active investments still have a role in a well-maintained portfolio for certain investors.

For example, while some active investments offer lower returns than their passive counterparts, the volatility associated with an index fund may be unappealing to some investors, says Phil McDonnell, vice-president and chief compliance officer at JRM Investment Counsel, a Nebraska-based adviser. After all, he says, large-cap equity markets have experienced several periods of substantial loss over the past 80 years. For example, the value of the S&P 500 dropped by more than half between October 2007 and March 2009.

“The amount of financial risk someone can afford to take doesn’t always match the amount they can emotionally withstand,” Mr McDonnell says. For these risk-averse investors — such as individuals nearing retirement or charitable foundations and endowments — active funds that are designed to produce a steadier, though lower, return may be more palatable.

Additionally, a diversified portfolio would typically include other asset classes that cannot be easily or efficiently managed passively because of a lack of infrastructure or liquidity. These include alternative assets, high yield credit, municipal bonds and real estate, as well as investment in developing markets, Mr McDonnell says.

Some advisers expect active investments to stage a comeback sooner or later. Several active managers have cut their fees to compete with cheaper passive investments, says James Sullivan, managing director of New Jersey-based Private Advisor Group. “I don’t see it so much as active versus passive. I see it as low cost versus high cost,” he says. “Both the passive management discussion and the Department of Labor’s [fiduciary] rule seem to be wringing the cost out of the system.”

The fiduciary rule, introduced on June 9, tightened the requirement that investment advisers must act in the best interest of their clients. Advisers now face additional scrutiny on fees and will have to explain themselves if they have not chosen the best deal for clients.

This would appear to favour yet more switching from costlier active funds. Abby Salameh, chief marketing officer at Private Advisor Group, argues more competitive pricing will be needed to staunch the flow of assets out of active funds.

“We think that’s going to shrink the marketplace and compress costs even more for advisers and clients. Advisers are ultimately going to have to justify their fees and value proposition to clients,” she says.

A question hanging over passive investments is that their popularity is yet to be tested by a severe market downturn, and advisers are unsure what effect a recession would have. The vast majority of flows into index funds have taken place since the global financial crisis of almost a decade ago.

Such circumstances would highlight the qualities of good active managers who might be better thought of as risk managers, says Brian Flynn, vice-president at Dynasty Wealth Management, a New York-based adviser.

“Since 2009, the markets have continually gone up. This is the same period where we’ve seen tremendous fund flows to low-cost ETFs and we really haven’t had any market correction,” he says. “I think you put risk management on yourself as a [passive] investor. If you’re doing it yourself and in a passive fund, there’s nobody behind the scenes taking that risk off the table.”

Comments